The following article, by HLAA’s Larry Guterman, takes an inside look at the making of the Oscar-winning movie “CODA”, and also appears in the fall issue of Hearing Life Magazine.

Few cultural phenomena have brought attention to the community of people with hearing loss —– which includes people who are Deaf or hard of hearing —– to the extent that the 2022 Oscar-winning movie “CODA” has. It’s the first film to win an Oscar where three of the main characters are Deaf.

Few cultural phenomena have brought attention to the community of people with hearing loss —– which includes people who are Deaf or hard of hearing —– to the extent that the 2022 Oscar-winning movie “CODA” has. It’s the first film to win an Oscar where three of the main characters are Deaf.

The film won three Oscars

- Best Picture

- Best Adapted Screenplay for writer and director Sian Heder

- Best Supporting Actor for Troy Kotsur

“CODA” is an acronym meaning “Child of Deaf Adults,” and the film focuses on daughter Ruby, played by Emilia Jones, who is the only hearing member in a Deaf family.

Some say the popularity of “CODA” has launched a movement for the invisible disability of hearing loss, as the film’s powerful dramatic story was brought into the mainstream. Suddenly, everyone is talking about the challenges of hearing loss, as the heartwarming coming-of-age story played out on the big screen.

Film director Larry Guterman, who lives in California, has served on the HLAA board of directors, and has severe hearing loss. He recently interviewed director Sian Heder, who adapted “CODA” from a 2014 French film. The two directors compared notes on movie-making, which both dryly observed, can be a bit like going to war. Guterman also brought his own experience contending with hearing loss to the discussion, as the two delved into why this film speaks to so many of us.

Larry shared some highlights from his discussion with Sian over Zoom in July.

A Chat with Director Sian Heder

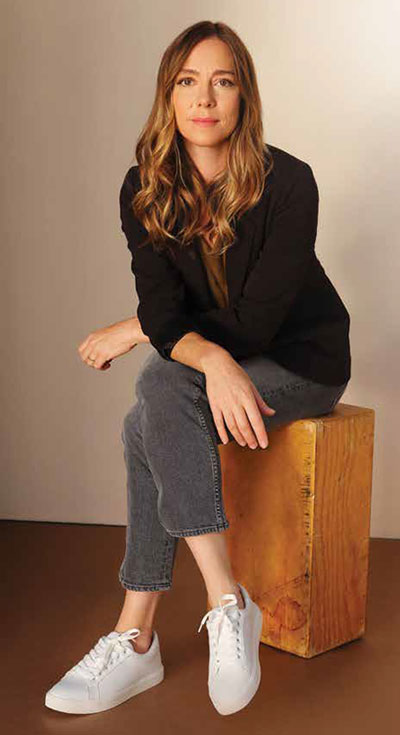

Sian Heder sits in a room in her Gloucester, Massachusetts home, a working-class town that is the setting of her film, “CODA,” the movie that won the Oscar for Best Picture and Best Screenplay, which she wrote and directed. She purchased the house, close to where she grew up, after the film. She admits the emotional tug of the movie, set in this working-class town, is not lost, even on her.

“Every time I watched it (during post-production), I cried. My editor would say to me, ‘stop it already! When are you gonna stop crying? You’ve seen it 1,000 times,’” Heder admitted.

At age 45, after years of dogged determination and perseverance trying to get the movie made despite seemingly impossible odds, Heder is the picture of calm and level-headed strength, over our Zoom call. She seems to have taken the incredible the success in stride. This master of her craft says the real rewards are the validation of her peers, and especially the impact her work has had on the marginalized and those who’ve had to struggle. She’s driven by a fierce determination to tell stories that have an impact in the world, and “CODA” achieved this in stunning, unassuming fashion.

A Familiar Story

The 2014 French version of the film used actors who did not have hearing loss, but Heder says she loved the simplicity of the story, about a girl growing up and breaking away from her family. She wanted to tell the story in a way that portrayed Deaf characters more authentically.

“This is just a kid leaving home. What I was interested in was, within that framework, the exploration of all the unfamiliar, which was looking at a family that we have never looked at before in this way. I think audiences (these days) are more open to all these kinds of unfamiliar things, like sitting in silence for a long portion of the movie,” explained Heder.

As a fellow director, I asked her about the risks of remaking a film, about taking that leap. Heder said she was intrigued by the chance to explore a kind of family dysfunction that she had never seen before — one where the more mundane daily struggle was complicated by the tension between Deaf culture and the hearing world.

“I’m really drawn to stories about outsiders, or people who have been marginalized, or communities which haven’t really been portrayed as the leads of a story. I thought it had so much potential cinematically. The original film was treated in a lighthearted way, so in a lot of ways it was very ripe to make another movie, because I thought, well, here’s this very deep premise,” she shared.

In the movie, Ruby nears the end of high school and begins to entertain her dreams of going to a renowned music college for singing. She struggles with breaking free from her Deaf parents and brother, who rely heavily on her as a translator for their fishing business, and they can’t relate to her love of singing. The family drama is set in a small fishing town near where Heder grew up. I asked Heder if she had a personal connection to hearing loss, or to the Deaf community before making the film.

“I did not have it before, and I deeply found it. As I was making the film, I knew going in that I was an outsider to this community, and if I was going to tell this story, I had to have collaborators from the community. There’s a saying within the Deaf community that I’m sure applies to any underrepresented community, which is ‘Nothing About Us Without Us,’ she explained.

“When I started researching the film, I immediately had… four key “CODA” collaborators who were sharing their experiences with me… The more that I understood and learned about Deaf community and culture, the more adamant I became about how the movie needed to be made. I knew that I wanted to have not only Deaf actors in these roles, but I also wanted to have 50% of the dialogue in American Sign Language (ASL), without having Ruby speak through all of those scenes, which is what was being pushed on me. I didn’t want to use music to fill up all of the silence,” she said.

Committed to Authenticity

The studio felt her choices were not commercial and wouldn’t appeal to mainstream audiences, and promptly dropped the project. The movie was dead for six months, until one of the supportive studio executives left and helped get it made independently.

Heder learned sign language for the movie and immersed herself in the culture through her collaborators. Everyone was on-board, including actress Marlee Matlin, who usually wears a hearing aid, but took it out for the movie to play Jackie Ross more accurately. Jackie is Ruby’s mom, who signs but doesn’t speak at all.

“I think that was my goal going in — to make a movie that honored Deaf culture, that really portrayed it in an authentic and nuanced way, but that also transcended it and made it about the experience of family,” Heder said.

Eventually, the movie was bought by Apple TV, allowing Heder to celebrate her choices that seemed risky at the time, including her choice of the high school concert scene where Ruby sings in her glee club performance. The audience experiences the scene from her Deaf parents’ point of view — in total silence, thus allowing hearing viewers to empathize with their daily struggle.

“It’s very validating as an artist to be like, ‘This is what I knew in my gut was not a conversation,’ and, sure enough, they are all the things that people have looked at as being unique about the movie,” Heder explained. “Down to the silent concert scene, which I was arguing with people about up until the final mix.”

Scenes like these are cinematic gold —– they speak not only to the hard of hearing, but also to hearing audiences —– they’re specific and universal —– artful, hopeful and uplifting.

Common Struggles

Heder even incorporated one of the most commonly frustrating experiences for people with hearing loss, a group conversation in noisy background chatter, that you struggle to follow. In the movie, Ruby’s brother Leo, played by Daniel Durant, who yearns to be accepted among his co-workers, struggles to lip-read when he goes to a local bar with them, but bluffs and laughs along with the jokes anyway.

The scene is shot from Leo’s perspective in the bar, and the shots mirror his point of view, making it impossible to follow what’s happening.

“If you watch this scene, the camera is on some- one’s lips, but then they drink a beer (blocking their lips)” Heder said. “Then someone else laughs across the table, the focus changes; next, Leo’s looking at a woman across the bar, and by that point, he’s tuned out and it’s like, ‘who cares anyway?’”

Heder shared that it was a variation on a scenario her collaborators described in excruciating detail, and it’s one I can certainly relate to. Our easy rapport discussing this experience illustrated her deep empathetic commitment to telling this story, which feels like everyone’s story who has a hearing loss.

I described my own experience to Heder, “I was at Thanksgiving dinner last year with strangers and for two hours, I was pretending to laugh and nod, and wondering, am I reacting appropriately? So, you’re having this weird out-of-body experience where you’re trying to engage with the person, and you can’t quite understand…and you’re also evaluating whether your persona and affect…is appropriate.”

It’s a feeling that Heder says she’s since experienced herself during rapid-fire group sign language conversations, struggling to follow along and sometimes pretending to understand, and eventually becoming exhausted, and giving up.

She expressed her surprise, even indignation, at, “the amount of work that is asked of people who have a disability to…play along, to make do in the world, without anybody bending or changing their behavior to sort of accommodate you.”

She was committed to creating a scene that immersed the viewer in the daily struggle people with hearing loss contend with. Scenes like these are cinematic gold — they speak not only to people with hearing loss, but also to hearing audiences — they’re specific and universal — artful, hopeful and uplifting.

New Perspective

Heder explains, “I think the experience of making “CODA” has also helped me understand how sort of barren the field of representation has been in terms of the Deaf and hard of hearing community, and the disability community in general. So, I’m also very invested as a storyteller, in continuing to tell these stories.”

As a director with hearing loss, I can’t thank Heder enough for her commitment to telling a story about disability in which everyone can feel included — a beautifully crafted, funny, empathetic work that touches the soul.

Stay tuned to HLAA’s Hearing Life e-news and social media channels for video clips and more details of my interview with Sian Heder.

You can watch “CODA” on Apple TV+.

Larry Guterman is a feature film director (“Cats and Dogs” for Warner Bros., “Antz” for Dreamworks), who also has severe hearing loss. He has served on the HLAA board of directors and is co-founder of SonicCloud, a technology company dedicated to personalizing sound on phones and computers for people who have hearing loss. Email Larry at larrygute@gmail.com.

Larry Guterman is a feature film director (“Cats and Dogs” for Warner Bros., “Antz” for Dreamworks), who also has severe hearing loss. He has served on the HLAA board of directors and is co-founder of SonicCloud, a technology company dedicated to personalizing sound on phones and computers for people who have hearing loss. Email Larry at larrygute@gmail.com.

For questions, contact HLAA at inquiries@hearingloss.org.

Enjoyed this post? Never miss out on future posts by following us.

Follow HLAA and “Like” us on Facebook today!